Who’s Responsible for This Thing? From Design to Disposal, EPR Says Manufacturers Are

Who’s Responsible for This Thing? From Design to Disposal, EPR Says Manufacturers Are

Written By

Crushed plastic bottle on grass. Photo by Karolina Grabowska on Pexels.

There is an idea gaining traction around the world: manufacturers should be held responsible for designing products that use less plastic and harmful materials, and for disposing of them when they reach their end of life. Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) laws are the embodiment of this concept, and they are becoming more popular by the day.

First proposed in Sweden in 1990 by Thomas Lindhqvist, EPR is based on the “polluter pays” principle. In its most basic form, it is the idea that the manufacturer, aka the producer, should be responsible for its products for the entire lifecycle of its products. From design to disposal, under EPR laws producers are responsible for it all…in theory.

How EPR works

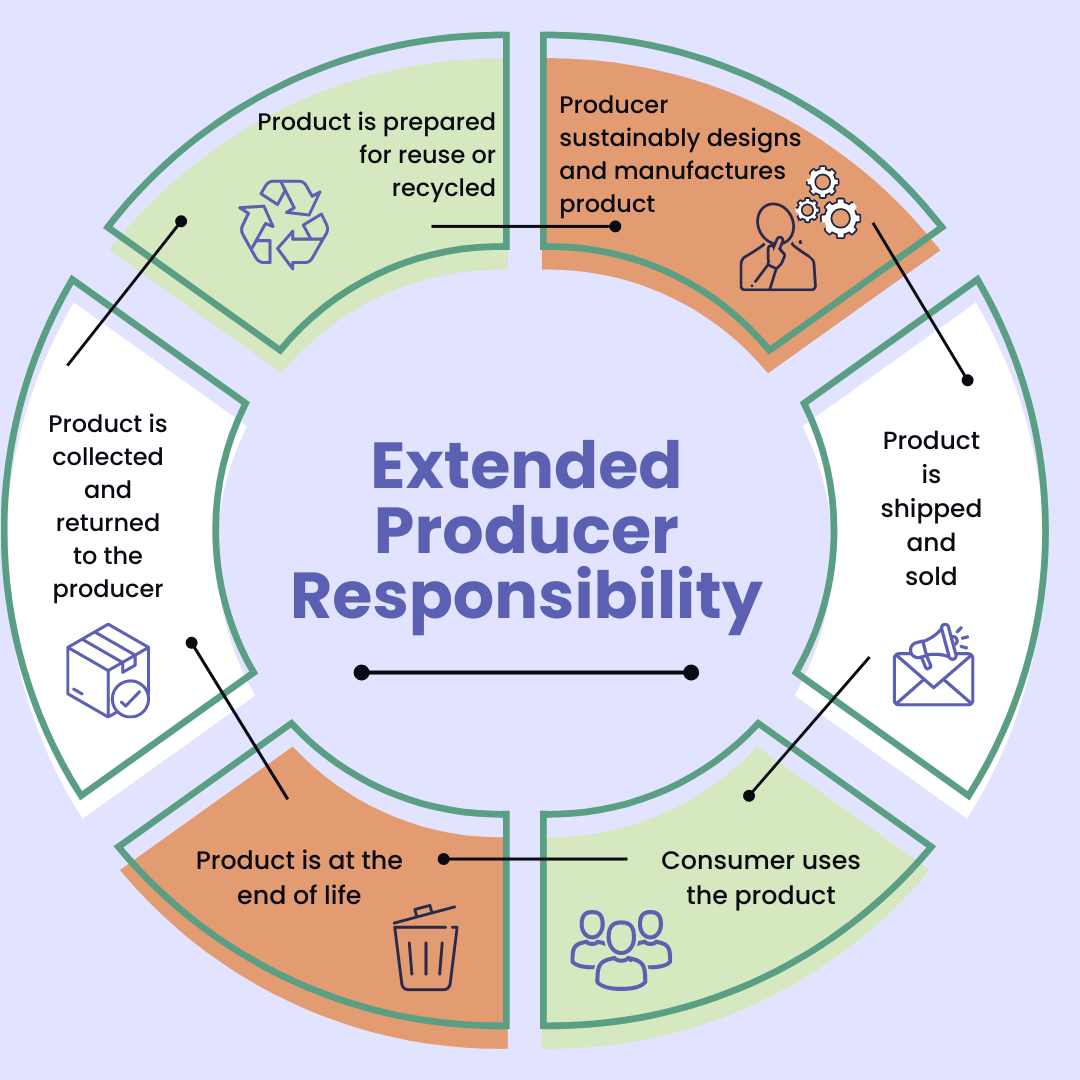

EPR laws and initiatives vary by nation, state, and even community. However, one model has emerged that has proven popular for the implementation of EPR. The simplified version is:

The extended producer responsibility cycle. Infographic by Dargan Gilmore.

- Manufacturers design and produce a product. Ideally, this is where EPR first comes into play. The ultimate goal of EPR is to influence the design of products to require less new extraction of materials from the earth; use less plastic and toxic or otherwise harmful chemicals or substances; be repairable and/or reusable; and require less packaging.

- Then they have to sell and ship the product. EPR plays a role here by making producers pay higher fees for products requiring lots of packaging. Less packaging, lower fees; more packaging, higher fees.

- Next, the consumer uses the product, preferably until it reaches its end of life.

- If and when a product does reach its absolute end of life, under EPR the manufacturer is responsible–at its own cost–for taking back (collecting) and properly disposing of it in a way that is not harmful to humans, animals, or the earth. In the best case scenario, this entails reusing the product and/or its component parts; for example, mattresses can be broken down and most of their parts reused in other products. If reuse is not possible or is hazardous–as, for example, expired medications or used medical supplies may be–the manufacturer must determine the best and safest method of disposal.

How can manufacturers accomplish all of these responsibilities? One way is via Producer Responsibility Organizations (PRO). PROs are organizations, usually nonprofits, formed by manufacturers for the purpose of collecting and treating waste and performing administrative tasks and funding activities, such as charging fees to pay for the work that must be done. PROs are “the primary means by which producers seek to meet their [end-of-product-life] responsibilities under EPR.”

This model of EPR is not without its imperfections (see below), nor is it the only model extant. It is, however, one of those seen most often regardless of location.

And speaking of location, just how popular is EPR?

EPR Around the World

World map string art. Photo by Monstera Production on Pexels.

As of 2013, all 28 Member States in the European Union (EU) (that is, all 28 nations that were members of the EU at the time) had at least one form of EPR in place, and many had several kinds. Today, at least seven Latin American countries–including Brazil, Colombia, Chile, Costa Rica, Peru, the Dominican Republic, and Uruguay–also have various types of EPR laws or frameworks in place, as do India, Japan, and the Republic of Korea. Canada has multiple EPR programs as well.

So what about the US?

EPR in the US

In the United States, paint and electronics were some of the first consumer products for which EPR laws were passed. The initial goal was to give government a voice in determining funding models for the management of products at the end of their life. Oregon was the first state to pass such a bill in 2009, and today 11 total states and the District of Columbia have EPR laws regarding paint. This initiative shows how it is possible for governments to successfully partner with producers and retailers to begin recycling programs for these products, and they are a success with consumers.

But paint and electronics are not the only products out there, and many states have tried to pass similar bills with regard to those items–with varying degrees of success. From 2021-2023, a total of 13 US states, including North Carolina, introduced bills containing EPR provisions. Only four states–California, Colorado, Oregon, and Maine–passed such bills. However, at the time of writing, four additional states have already introduced bills for 2024, including New Hampshire, New Jersey, Washington, and Rhode Island, while North Carolina still has an active bill in committee known as “Break Free from Plastics and Forever Chemicals” or HB 279. In Congress, the “Break Free from Plastic Pollution Act” was re-introduced in 2023 after failing to advance in 2020 and 2021. The bill is currently in committee in the Senate.

EPR in North Carolina

Statues of wolves at North Carolina State University. Photo by Dargan Gilmore.

In North Carolina, the 2009 Discarded Computer Equipment and Television Management Law established that responsibility for the collection and disposal of electronic equipment should be shared between producers, retailers, state and local governments, and consumers.

Today, HB 279 proposes the following EPR program with a wider scope:

- Requires manufacturers to establish or join an existing PRO to act on their behalf

- Prohibits manufacturers from selling products with packaging unless they’re a member of a PRO with a stewardship plan approved by the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ). Before even submitting the plan to DEQ, the producer has to give the public and any stakeholders the opportunity to review and comment on the draft.

- Establishes 12 types of information that must be included in the plan, such as:

- A description of how the packaging materials the plan covers will be collected and managed via environmentally-sound practices

- A proposal for conducting an outreach and education program that increases recycling access throughout the state

- A description how collectors will recoup reasonable costs from the PRO for collecting, transporting, or sorting the packaging the plan covers.

- Requires producers to reduce the total amount of non-reusable packaging material

- Requires PROs to calculate and disperse funds to collectors for recovering, recycling, and processing packaging

- Requires PROs to have participation fees and establishes guidelines for those fees, including the requirement that the fees provide manufacturers with financial incentives to reward waste reduction.

- Requires PROs to maintain a producer responsibility fund comprising the payments received from participating manufacturers. This money will, among other uses, pay for the required outreach and education programs as well as the PROs’ operating costs.

- Requires manufacturers to label packaging with (1) its percentage of postconsumer waste material content, (2) whether the material is readily recyclable, and (3) whether the material is compostable.

EPR Goes Local

Outdoor rusted spring art installation. Photo by Kerstin Riemer from Pixabay.

On a local level in the Triangle, Wake County has launched a shredder program for mattresses. The mattresses are brought to the South Wake Landfill, where they’re shredded and then buried in the landfill. To cover operation costs, the county charges a fee of $10 per mattress or box spring. While the county is aware of how mattresses can be recycled, currently it is choosing to shred them while planning to expand to recycle and reuse mattress materials in the future.

Criticisms of EPR

EPR implementations have not always been perfect solutions. There is limited evidence, for example, that product designs have changed to improve circularity and sustainability. It is likely that the more granular fees necessary to properly incentivize such design changes would result in “increased complexity and administrative burden and resulting costs.” Without such incentives, producers may focus more on some aspects of EPR–such as recycling–than on designing products that don’t require it.

In addition, there is the question of whether industry should be in charge of PROs. With many companies making shareholder value their main goal, the profit motive can result in prioritizing profit margins over the needs of the environment.

And there have been instances where EPR has limited the amount of business that small, independent operations receive if they are not members of the PRO, such as Oregon-based nonprofits NextStep and FreeGeek. In that instance, EPR laws led to the centralization of e-waste collection by a smaller group of companies of which the two nonprofits were not a part. This impacted NextStep and FreeGeek by reducing their business, and it also reduced the number of available jobs and opportunities to learn new skills in reuse and repair.

The lessons from these flawed implementations of EPR are clear: there must be a balance between effective EPR laws and socioeconomic growth in communities, including the Right to Repair.

What You Can Do

There are many ways in which individual consumers can take action regarding EPR. One way is by contacting your legislators to support existing EPR bills or request that such bills be created. Another is by creating and/or voting for pro-EPR shareholder proposals in companies in which you are invested as a shareholder activist. If those companies decline to adopt such proposals, vote with your dollars by divesting from them and avoid purchasing products from them and companies with similar stances. You can also contact local businesses, explain the EPR principles, and ask them to commit to working toward adopting such policies.

Open sign at a small business. Photo by Tim Mossholder on Pexels.

Are you a business owner in a location without EPR laws on the books? No need to wait for one; you can begin following the principles now by designing or redesigning your products to require less packaging and be repairable and reusable. Need to make a shipment? Choose the option with the least packaging. Work at or run a retail store? Show suppliers where you stand by declining to carry products that don’t meet EPR standards.